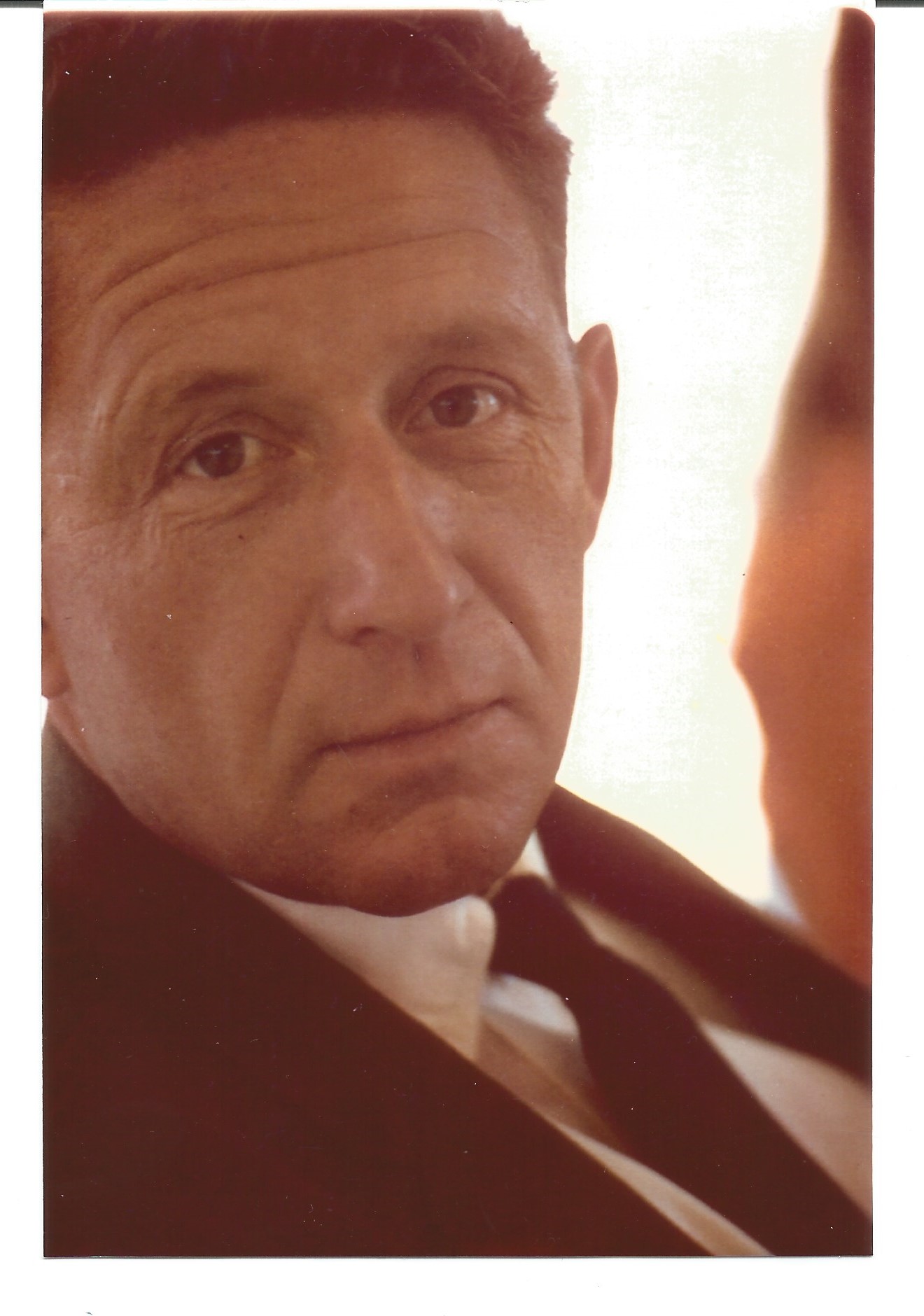

Charlie Hess’s Long Life of Adventure

by John F. Mencer (1978-2002)

The fascinating story of retired FBI Agent Charlie Hess began in the original Roaring ‘20s, a literal lifetime ago, and continues into the ‘20s of this, the next century. He has seen the Great Depression, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union, 9/11, and, now, a worldwide pandemic. Along the way, Charlie collected adventures of his own, some of which led to a book and a 2007 feature article in The New York Times Sunday magazine.

The fascinating story of retired FBI Agent Charlie Hess began in the original Roaring ‘20s, a literal lifetime ago, and continues into the ‘20s of this, the next century. He has seen the Great Depression, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union, 9/11, and, now, a worldwide pandemic. Along the way, Charlie collected adventures of his own, some of which led to a book and a 2007 feature article in The New York Times Sunday magazine.

Charlie was born to a tailor father and a seamstress mother in Al Capone’s Cicero, IL, in 1927. Cicero was a gangster haven then and wisecracks about the scent of gun smoke lingering in the air had a basis in fact. It was a tough place with its own set of rules. Charlie’s early exposure to “wise guys” was frequent and once included a chance encounter with two of their victims.

One school day in 1933, young Charlie and his best friend took a detour through an abandoned housing project filled with excavated pits intended to become finished basements before the Great Depression intervened. Nearly stumbling into one pit overgrown with weeds, the boys peered down to see it was filled by a large black sedan. The big car was riddled with bullet holes and, as they moved closer, the boys made out a blood-spattered face pressed hard against the driver’s side window. Most of the driver’s head was missing and his slain passenger was propped against him. The boys scrambled away in horror, never to forget the awful sight.

Concern over Cicero’s criminal element and similar incidents prompted Charlie’s father to move the family to a small resort area on Fish Trap Lake in Boulder Junction, WI. Far from the Cicero criminal element, Charlie experienced other adventures in the outdoors as a paid fishing guide and railroad worker.

In 1945, Charlie graduated early from high school and enlisted in the U.S. Navy, hoping to experience the adventure of a lifetime by battling America’s enemies. It didn’t work out that way, however, and, by the time the Navy shipped him to the Philippines, General MacArthur had fulfilled his promise to return. Charlie was left to pass time until his discharge in 1946.

Upon return, Charlie attended college, married his first wife, JoAnne, and fathered his first daughter, Chris. He worked at a high school in Grand Marais, WI, on the shores of Lake Superior, where he taught and coached football. Candy, his second daughter, was born there. As his football program grew, Charlie met other coaches, one of whom was Kenneth Puckett. Puckett became a friend, and, in 1952, he was hired as an FBI Agent. Charlie’s yearning for adventure had returned by then. That desire coupled with the financial constraints of a teacher’s salary prompted Charlie to reconsider career options. After learning that Puckett, who was neither a lawyer nor an accountant, was earning more than $5,000 per year, Charlie made a decision that changed the trajectory of his life. He applied to join the FBI through the Detroit Division and reported to the Old Post Office in Washington, DC, on March 31, 1952.

Training was much different in 1952. Charlie roomed at the YMCA for the first six weeks of class, and his final two weeks were spent at Quantico for firearms and defensive tactics training. The facilities, including the sleeping quarters, were formerly World War II-era Marine Corps barracks.

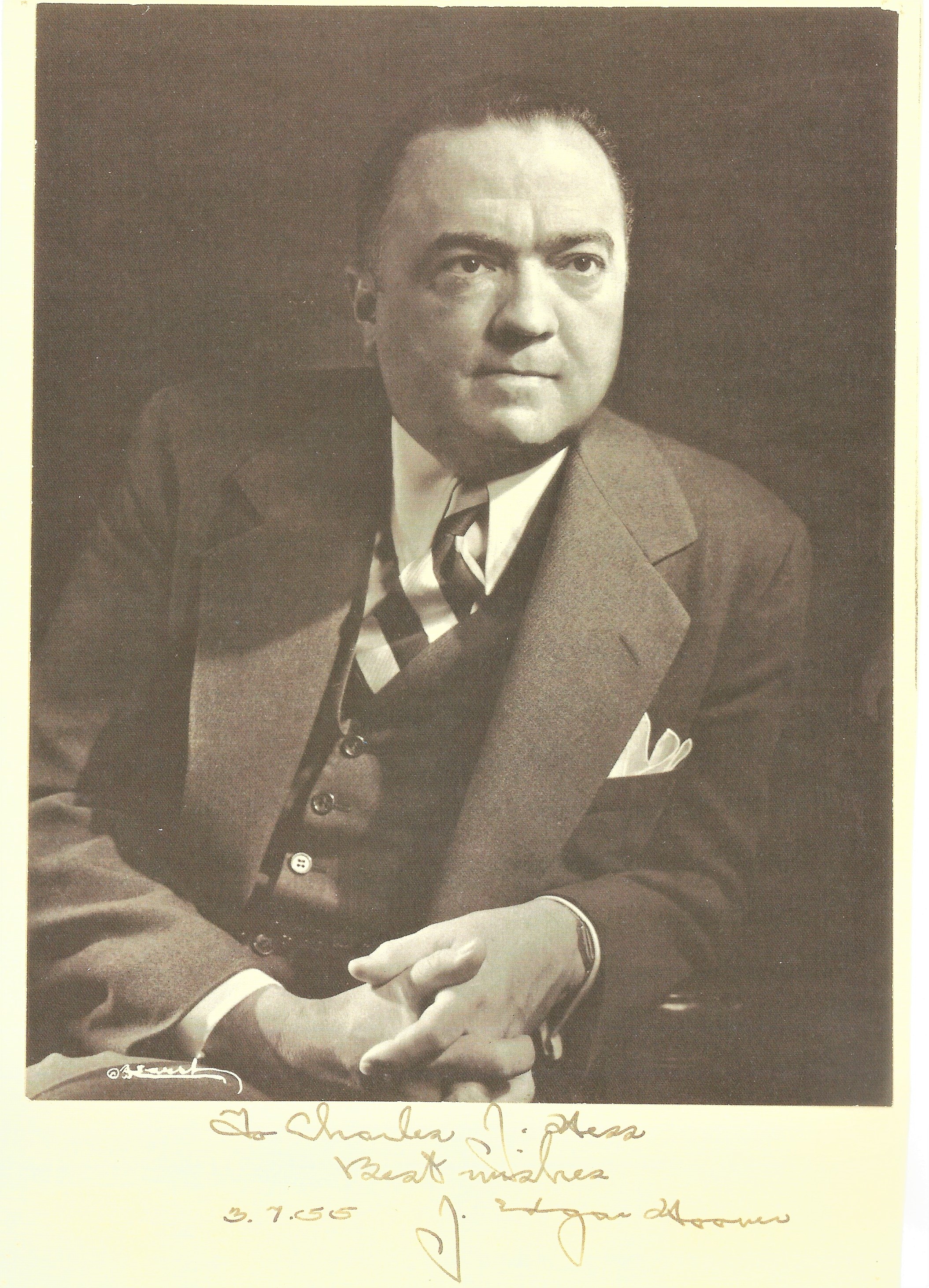

At graduation, Charlie met and shook J. Edgar Hoover’s hand for the first time, and soon gathered the family and left for his first office in San Antonio. There he was assigned a training agent, Supervisory Agent Dallas Johnson. (Note: Former SA Johnson lives in Dallas, TX, and turned 103 in February 2020). Johnson shepherded the new-minted Agent Hess around the division. After his period of field training, Charlie was assigned some cases and allowed to work on his own.

Charlie’s street smarts served him well, and it wasn’t long before he had developed 12 informants. Despite being a new Agent, his caseload was eased so that Charlie could focus on these relationships.

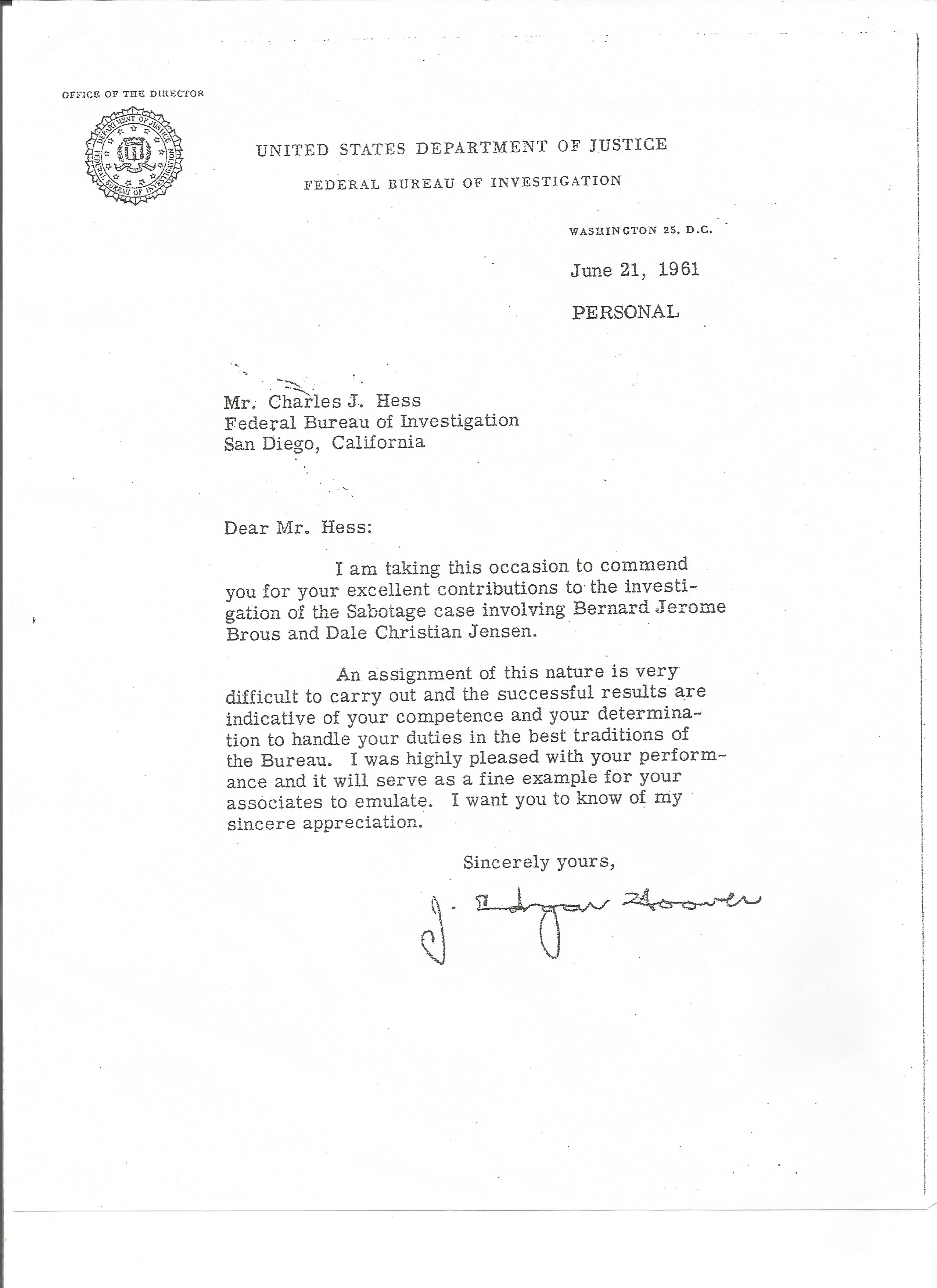

With his talent for building trust, Charlie’s Bureau career kicked into high gear and official recognition followed. Over the next ten years, his efforts earned him an impressive nine letters of commendation from Director Hoover. His first was earned for outstanding work in developing productive sources, but Charlie was also officially recognized for criminal and security case work.

With his talent for building trust, Charlie’s Bureau career kicked into high gear and official recognition followed. Over the next ten years, his efforts earned him an impressive nine letters of commendation from Director Hoover. His first was earned for outstanding work in developing productive sources, but Charlie was also officially recognized for criminal and security case work.

After San Antonio, Charlie spent time in the Alpine (TX) RA, language school, and San Juan. Then, it was on to San Diego. His success with sources resulted in recovery of a prominent kidnapping victim, the capture of an Identification Order fugitive, and the disruption of an anti-government Communist plot in Baja California.

Despite his successes, Charlie’s most noteworthy case proved to be the unexpected beginning of the end of his FBI career. In 1961, while working closely with the Baja State Police in Mexico, Charlie apprehended two saboteurs who called themselves “The American Republican Army.” Self-styled revolutionaries Bernard Brous and Dale Jensen had blown up radio towers in Nevada and Utah. In addition to causing serious damage to civilian networks, the loss of the towers caused the Navy to temporarily lose contact with the U.S. Pacific fleet.

When Charlie picked up the case, Brous and Jensen were piloting a boat in Mexico south of Tijuana. Reports were that it was laden with ammunition, machine guns, and explosives, and the pair were threatening more violence. When they stopped in Ensenada to refuel, Charlie and his colleagues were waiting.

Jensen was first off the boat and the surveilling Agents allowed him to move far enough away to make a discreet arrest. Brous was working on the boat deck when Charlie and the Agents made their next move. The surprised Brous was unarmed as the men rushed onboard, but he frantically grabbed for a weapon. The Agents tackled Brous as he tried to pull the pin from a live hand grenade. Their quick actions averted certain injury and possible death due to the dynamite cache they discovered filling the boat’s hull.

Bernard Brous had been accompanied by his wife, Minnie, who was believed to be unaware of the conspiracy. Minnie was very quiet, almost as if in shock. She had nowhere to go with Brous in jail, and so the Bureau Agents placed her into a hotel. Minnie was fully dependent on her husband and seemed unable to function alone. Not long after the arrests of Brous and Jensen, Charlie learned of Minnie’s suicide. He couldn’t comprehend why she gave up on her young life and, as time passed, Charlie burdened himself with blame for her death.

By 1962, Charlie’s penchant for risk-taking and adventure, and his guilt over Minnie’s suicide, aligned with a growing fondness for alcohol and a deteriorating marriage. As he did earlier in life, Charlie questioned his future.

One day, he went on a late night bender and didn’t show up for work the next morning. He concocted an excuse, but management took note. A few months later, Charlie stumbled again, but this time he didn’t bother with an excuse. The SAC offered Charlie a few options. One was a dreaded reassignment to New York, while the other was resignation. Charlie felt he had let the Bureau down and he didn’t want to go to New York, so he grudgingly allowed his FBI career to end only ten years after it began.

Charlie continued to drink, but it never kept him from fulfilling family obligations. He quickly found a job as City Manager in National City, a suburb of San Diego. The job was steady and kept him engaged in meaningful work. It lacked the excitement of law enforcement though and Charlie found himself growing restless again.

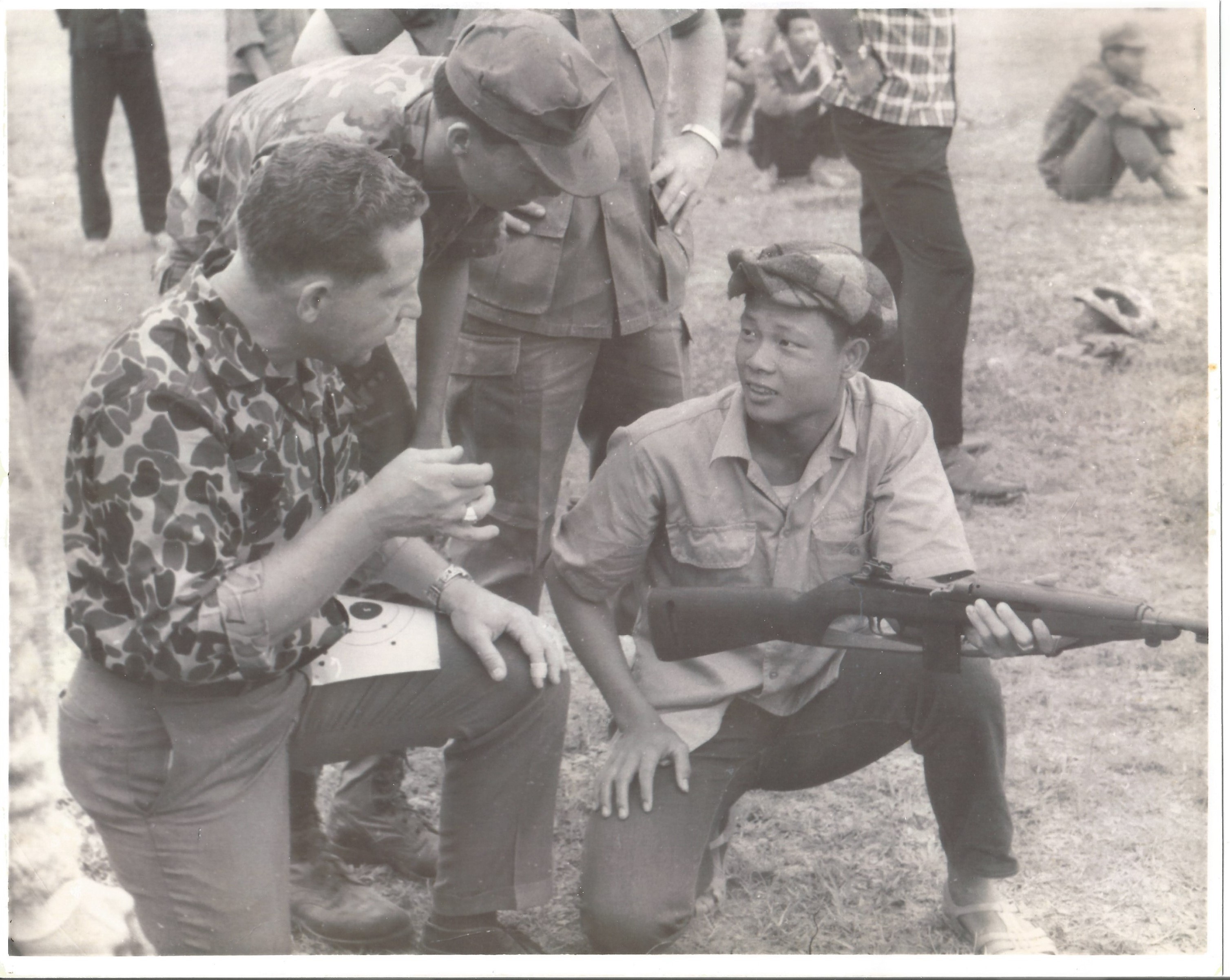

In the mid-1960s, much of the US Agency for International Development’s (USAID) mission was directed at improving social and economic conditions in war-ravaged Vietnam but, by 1967, President Lyndon Johnson wanted to improve counterinsurgency operations by blending civilian assistance with military operations under the CIA. When a friend of Charlie’s employed by USAID suggested another career change, Charlie signed up for yet another adventure.

After a crash course in the Vietnamese language in Hawaii, Charlie arrived in Vietnam in 1967. His initial duties included supervising the motor pool, the steno pool, and third country nationals. Everything changed when he was recruited into the “Phoenix Program,” which later became very controversial.

After a crash course in the Vietnamese language in Hawaii, Charlie arrived in Vietnam in 1967. His initial duties included supervising the motor pool, the steno pool, and third country nationals. Everything changed when he was recruited into the “Phoenix Program,” which later became very controversial.

Phoenix was designed to eliminate the Viet Cong infrastructure in the south. Working jointly, South Vietnamese and American operatives gathered information on suspected guerillas and sought to capture, convert, or, as a last resort, kill them. One of the more prominent CIA officers, John Paul Vann, whose exploits were recounted in Neil Sheehan’s “The Bright Shining Lie”, learned of Charlie’s FBI background and brought him into the program. Charlie was given the responsibility of neutralizing Viet Cong leadership and its covert support organization.

The controversy surrounding the Phoenix Program arose from its interrogation centers and assassination squads. Charlie knew of a center in his area, but never witnessed the actions there. His duties required frequent travel to different districts where he would meet and identify Vietnamese draft dodgers, deserters, and petty criminals who might be able to penetrate the Vietcong’s inner circle.

Charlie’s service in Vietnam ended not long after he developed a debilitating tropical disease that caused him to lose considerable weight. He couldn’t shake the malaise and, although not eager to return to his rocky marriage, the illness left him little choice. He departed Vietnam with regrets about the futile war effort there.

Back in San Diego, Charlie regained his weight and his health. He cut back on drinking, but the marriage to JoAnne didn’t survive and they divorced in 1969.

Not content with the solitary life, Charlie soon met Jo, a petite Italian girl who was the daughter of a professional fisherman. He fell in love and resumed life in San Diego with renewed purpose and vigor.

Throughout the 1970s, Charlie worked as a polygraph examiner and instructor and as a private investigator. During this time, Charlie was stricken by one of a string of heart attacks. As the 1980s approached, he reexamined his priorities and decided to seek a new adventure.

Charlie had been traveling to Mexico for years and knew Baja California well. He persuaded Jo to give Mexico a try, so they bought a VW microbus and set down roots in Bahia de los Angeles. They rented an island from a local family and erected a home 30 feet above high tide and 20 miles away from the nearest locals. They survived on $6,000 per year by working security at the Del Mar racetrack in California - coincidentally, the one favored by J. Edgar Hoover on his west coast visits. It was a simple but idyllic existence.

Charlie had been traveling to Mexico for years and knew Baja California well. He persuaded Jo to give Mexico a try, so they bought a VW microbus and set down roots in Bahia de los Angeles. They rented an island from a local family and erected a home 30 feet above high tide and 20 miles away from the nearest locals. They survived on $6,000 per year by working security at the Del Mar racetrack in California - coincidentally, the one favored by J. Edgar Hoover on his west coast visits. It was a simple but idyllic existence.

Family tragedy cruelly interrupted the couple’s simple, off-the-grid life on Christmas of 1991, when Charlie was on a supply run to San Diego. His daughter Candy’s husband, Steve Vought, had been shot when he surprised some youthful burglars in his Colorado Springs home. Steve died cradled in Candy’s arms outside in the yard.

Stunned, Charlie and Jo rushed to Colorado Springs to support Candy. Steve’s murder was resolved quickly, and the killers were apprehended and convicted. Nonetheless, Charlie and Jo permanently left Mexico and built a small house on Candy’s property to be near her.

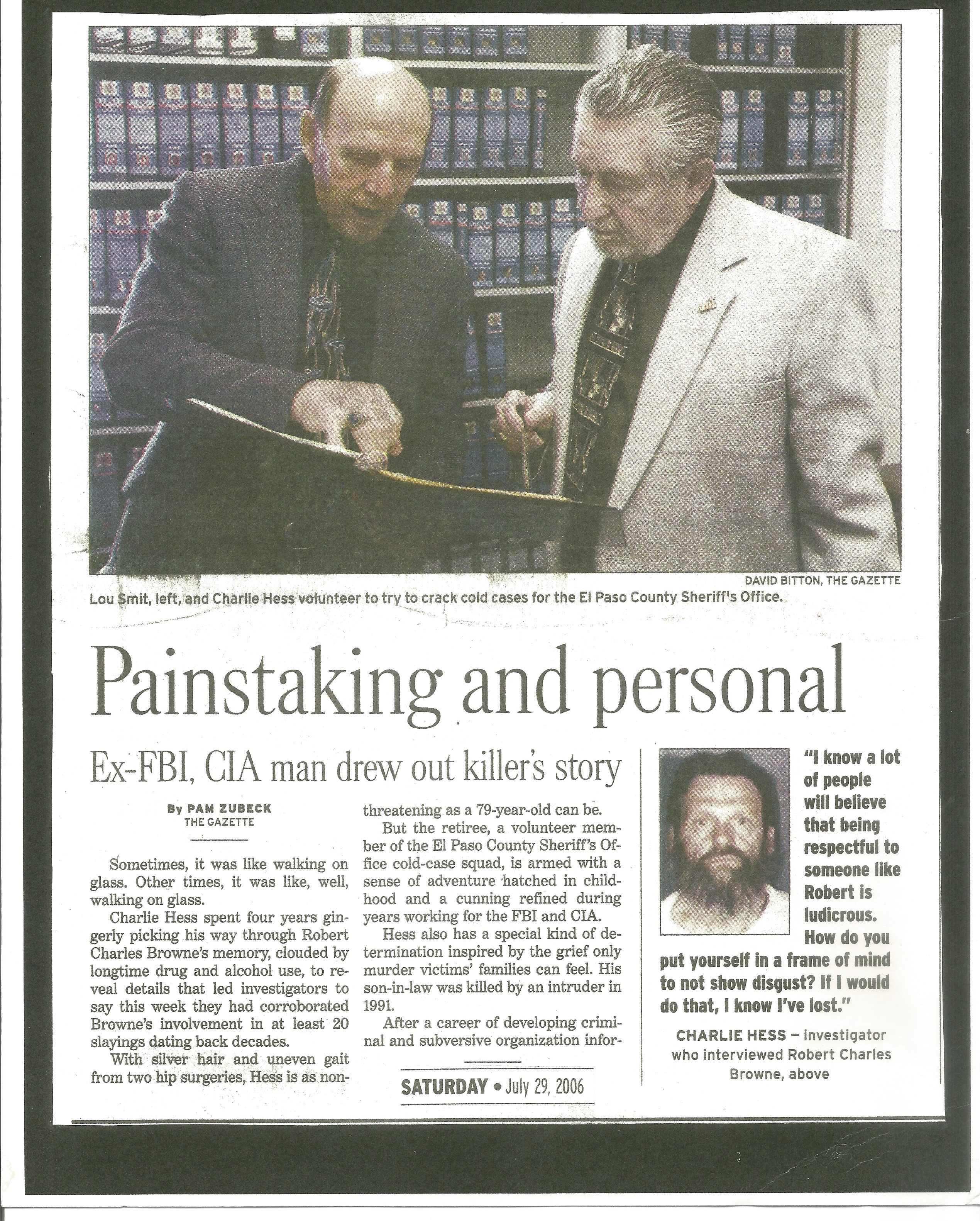

During this time, Charlie grew close to members of the El Paso County Sheriff’s Office (EPSO). One of Sheriff John Anderson’s innovative ideas was to create a cold case squad. Brimming with a renewed desire to be part of law enforcement again, Charlie volunteered to join Scott Fischer, a retired newspaper publisher, and nationally known detective Lou Smit in the undertaking. Smit would be called on to consult on the notorious Jon Benet Ramsay case several years later. The threesome became known locally as the “Apple Dumpling Gang,” a nickname taken from the 1975 comedy starring Bill Bixby, Don Knotts, and Tim Conway. Charlie was back in a familiar place again as he entered his next chapter.

The Gang enjoyed numerous successes, with the most prominent one featuring Charlie and his indefatigable efforts to convince reputed serial killer, Robert Browne, to confess to his many unsolved murders.

Browne was a neighbor of 13-year-old Heather Dawn Church, whom he killed in El Paso County in 1991. It was a notorious murder that Denver Division FBI Agents from that era remember because it took more than two years to find the youthful victim’s remains and nearly another two to identify, arrest, convict, and incarcerate Browne.

Browne, a drug and alcohol-abusing Vietnam veteran, was no stranger to law enforcement. He was linked to acts of animal cruelty, drug use, burglaries, and arson. Despite killing young Heather, Browne wasn’t on the Gang’s radar until, one day, Charlie casually asked Lou Smit if he had ever worked on a case in which the subject could have been a serial killer. Smit replied “yes” and, without hesitation, named Robert Browne.

His curiosity was piqued, and so 75-year-old Charlie Hess went to work on Browne. He learned that Browne exchanged letters with EPSO authorities. One included a cryptic four-line poem alluding to something sinister in Browne’s past, something beyond the Heather Church murder. In another letter, Browne included a hand-drawn map that outlined nine states with a number written in each. Added together the numbers totaled 49. Could that have been Browne’s victim count?

Charlie was intrigued by Browne’s letters and, on May 9, 2002, he wrote a letter of introduction asking Browne if he would like to talk about his earlier correspondence with the EPSO. As a way of establishing trust, Charlie included his home address in the letter.

The cat and mouse game began a week later with Browne’s reply. In it, he declined a personal interview, but dangled the prospect of cooperation by asking Charlie what he wanted to discuss. Charlie’s response noted that Browne’s letters resembled the way in which serial killers like Ted Bundy, Henry Lucas, and Otis Toole had opened their dialogues with law enforcement. Was Browne trying to “clear up some pending matters?” Was he seeking redemption by providing his victims’ families with closure? Browne remained tight-lipped.

They corresponded back and forth as Charlie pursued a rapport with each letter. In one, Charlie included a picture of himself holding a yellowfin tuna caught in Mexico. This prompted a complaint from Browne about the basic lack of protein in his prison diet, but he didn’t offer any information of value.

By September 2002, Hess was facing the first of two hip replacement surgeries and he urged Browne to give him some concrete details about other killings in case Charlie, at 75 years of age, didn’t survive the operation. Browne was impassive.

Soon after, however, Browne decided to bargain. He wanted something in exchange for his information. Charlie pushed back and questioned Browne’s credibility, as did the entire EPSO. They continued in stalemate, each seeking an edge. Browne finally offered some details about the 1984 murder of a young waitress in Flatonia, TX. The information was mostly verifiable and gave Charlie some hope. A few months later, a five-page letter from Browne included text to match the nine-state map that he had sent to EPSO years before. Each highlighted town on the map was accompanied with information about the burial site of a murder victim.

Soon after, however, Browne decided to bargain. He wanted something in exchange for his information. Charlie pushed back and questioned Browne’s credibility, as did the entire EPSO. They continued in stalemate, each seeking an edge. Browne finally offered some details about the 1984 murder of a young waitress in Flatonia, TX. The information was mostly verifiable and gave Charlie some hope. A few months later, a five-page letter from Browne included text to match the nine-state map that he had sent to EPSO years before. Each highlighted town on the map was accompanied with information about the burial site of a murder victim.

The problem was that much of the information Browne provided was publicly available. Charlie pushed harder, seeking singular information about local cases where they might find a body. Browne continued to hold back and, after his 14th letter, in July 2003, stopped writing. Charlie waited through the summer and, in September, he wrote Browne, but received no reply. Charlie didn’t try again until February 2004, when he was met with more silence. Seven long months passed before Charlie decided to make one last try - this time in person.

On September 9, 2004, more than two years after their initial correspondence, Charlie paid a surprise call on Robert Browne at the Colorado State Penitentiary in Canon City. His gambit worked. Browne awkwardly accepted Charlie’s handshake and a dialogue ensued.

Browne complained about food and the prison’s lack of adequate medical treatment while Charlie patiently let him vent. Browne had his audience and was determined to make the best of it. In exchange for details of his crimes, Browne’s “quid pro quo” included a medical exam by independent doctors and a transfer away from Colorado prisons. Charlie made no promises but offered to see what he could do.

Browne gave more information about the Flatonia murder, including his use of ether and an ice pick to kill his victim, Melody Bush. Actual progress was finally being made.

Due to his second hip surgery, Charlie put off his next visit until December. Again, the personal touch proved effective and Browne offered details about a second Texas murder in which he dismembered the 17-year-old victim, Nidia Mendoza, in a motel and carried her remains out in a suitcase. Browne described the dismemberment process in vivid, but clinical, dispassionate detail. Charlie fought revulsion to continue listening.

Information from Browne came in piecemeal fashion, but, in late January 2005, the dam suddenly broke. This time, Browne effusively described the 1983 screwdriver killing in Louisiana of next-door neighbor Wanda Faye Hudson. He described using a can of red ant killer containing chloroform to disable Hudson before stabbing her more than 25 times. Browne cleaned himself up afterward, repainted her apartment walls, and finished by sleeping in Hudson’s bed that night.

The EPSO was making steady progress with Browne now, but their jurisdiction was limited, and they were still keen on finding a local victim. During one of Browne’s earliest letters to Charlie, he cryptically referred to a murder that involved the “Grand Am lady” in El Paso County, but authorities made no headway with that slim lead. Charlie pressed on, and dangled Browne’s desire to be transferred to another state as leverage.

Using a map of Colorado Springs, Browne pinpointed an apartment complex where the victim lived in 1987. Browne met her when she and her husband rented video games from a convenience store where Browne worked. One fateful night in the store, the woman told Browne she had separated from her husband, and that he and their baby were out of state. Browne invited her to a movie that night. Afterward, they returned to his apartment in her white Pontiac Grand Am, and Browne strangled her and dumped her body in the bathtub. He then took her car, drove to her apartment, and stole a color TV. Browne returned to his apartment, slept there that night, and dismembered the young woman in his bathtub the next day. He disposed of the body in a dumpster, used her car for a few days, and left the white Grand Am parked near her apartment where he knew it would be found eventually.

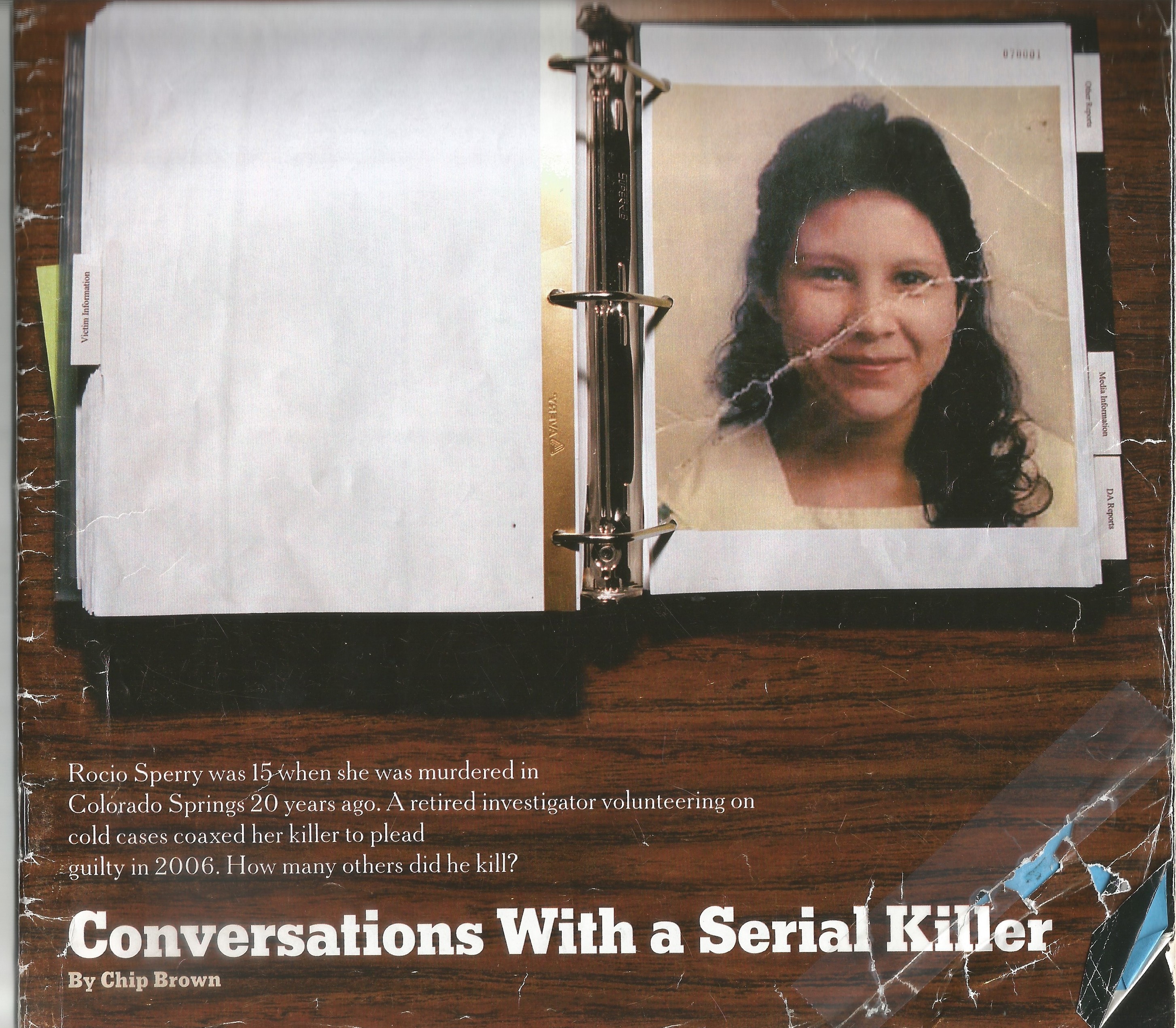

Using the white Grand Am clue, Charlie and EPSO detectives tried to find the car’s owner through stolen car reports. They ran into a dead end until one of the detectives, Rick Frady, recognized that one of the VIN numbers had a misplaced character. Digging deeper, Frady learned that the actual VIN led to a car owned by a Joseph Sperry. Sperry was tracked to Palm Beach, FL, where he confirmed he had owned a white Grand Am in 1987. To top it off, Sperry produced a case number for a missing person’s report filed on his wife with the Colorado Springs PD in 1987, one which the cold case investigators had been unable to locate in their numerous records searches. Sadly, Joseph Sperry and his wife, Rocio, had tried to save their marriage by separating shortly before her murder in November 1987. Rocio Chila Delpilar Sperry was only 15 years old at the time of her violent death and was the mother of an infant daughter.

Using the white Grand Am clue, Charlie and EPSO detectives tried to find the car’s owner through stolen car reports. They ran into a dead end until one of the detectives, Rick Frady, recognized that one of the VIN numbers had a misplaced character. Digging deeper, Frady learned that the actual VIN led to a car owned by a Joseph Sperry. Sperry was tracked to Palm Beach, FL, where he confirmed he had owned a white Grand Am in 1987. To top it off, Sperry produced a case number for a missing person’s report filed on his wife with the Colorado Springs PD in 1987, one which the cold case investigators had been unable to locate in their numerous records searches. Sadly, Joseph Sperry and his wife, Rocio, had tried to save their marriage by separating shortly before her murder in November 1987. Rocio Chila Delpilar Sperry was only 15 years old at the time of her violent death and was the mother of an infant daughter.

Browne provided enough details about Rocio Sperry’s murder to remove any doubt that he was the killer, but without a body, there was no guarantee of a murder conviction. Fortunately, Browne decided to plead guilty and remove all concerns. Charlie believes the plea was likely due to Browne’s desire to be transferred into the Minnesota prison system. Ironically, the plea in 2006 didn’t result in Browne’s transfer, but it did reunite 19-year-old Amie Sperry, Rocio’s daughter, with her father. Amie had grown up suspecting that her father, Joseph, had killed her mother. Browne’s plea ended that sad belief and resulted in a joyful reunion of father and daughter.

Browne claimed credit for 48 killings in all and provided details about more than 20. Some of his recollections were unable to be verified and no bodies were found. Without corroborating details and bodies, Browne’s claims drew legitimate skepticism. Did he concoct those claims to gain an elevated status in the warped pantheon of serial killers? Did he hoodwink Charlie, Lou Smits, and the EPSO team in the process, at least in part? One certainty is that Browne’s plea ensured his imprisonment for life. Perhaps it is small comfort to the families of his victims, but a comfort, nonetheless. For his diligence and stellar efforts in his dogged pursuit of Browne, Charlie was named “Volunteer of the Year” by the EPSO and awarded the Medal of Merit from the State of Colorado.

The Apple Dumpling Gang dissolved shortly afterward, mainly because Scott Fischer and Lou Smit left Colorado Springs to begin their own next chapters of life. With the arrival of a new County Sheriff, Charlie left, too. As 2007 unfolded, the NY Times featured an article about Charlie in April, but his beloved wife, Jo, had grown sick and passed away in October. Filling the void created by Jo’s death and the breakup of the Gang, Charlie co-authored a book about his many experiences, with much of the focus on Robert Browne. “Hello, Charlie” was published in 2008 and recounted the Browne case along with other tales of Charlie’s long and eventful life.

The Apple Dumpling Gang dissolved shortly afterward, mainly because Scott Fischer and Lou Smit left Colorado Springs to begin their own next chapters of life. With the arrival of a new County Sheriff, Charlie left, too. As 2007 unfolded, the NY Times featured an article about Charlie in April, but his beloved wife, Jo, had grown sick and passed away in October. Filling the void created by Jo’s death and the breakup of the Gang, Charlie co-authored a book about his many experiences, with much of the focus on Robert Browne. “Hello, Charlie” was published in 2008 and recounted the Browne case along with other tales of Charlie’s long and eventful life.

Charlie’s world eventually normalized, and he began attending a singles group for people over the age of 50. There, he met Patti McFarland, a bright, retired foreign language teacher with a passion for crime fiction. Sparks flew and soon the pair were happily linked as partners on the new Colorado Springs PD Cold Case squad and, eventually, in marriage. There remained many unsolved murders to review, and the couple found much satisfaction in mutually exploring cold cases together. Time rendered its inevitable verdict after a few years there and Charlie finally quit the last phase of his law enforcement career at age 85.

Today, Charlie and Patti spend most of their time in and around Colorado Springs. Charlie’s concession to age is minimal despite his health issues. He admits his memory isn’t what it once was, but he retains his wit, spirit, and some mischievous charm. It’s the hallmark of an extrovert that leaves no doubt of his well-honed skills as a top notch informant man who, in his later years, became the confidant of a serial killer.

John Mencer (1978-2002) served in the Newark, FBIHQ, and Denver Divisions. He was a member of the Foundation’s Board of Trustees from 2012-2015, and Chairman for the last two years.